maj Juha Kukkola, D.Mil.Sc., Assistant Military Professor, Russia Research Group, Finnish National Defence University

This text concerns a dual problem the Western researchers of Russian Armed Forces have been trying to solve for the past two years, namely: Why the Russian offensive against Ukraine in February 2022 failed and what kind of lessons Russia could draw from the war when it eventually starts to rebuild its Armed Forces for future wars. Many different explanations for Russia’s failure have been offered by established scholars and pundits alike. This text is not about trying to find out who is right or if there is one single overriding cause for the Russian failure. What I will try to briefly examine is how these explanations fit together and what are the difficulties we face when we try to explain something as complex, ambiguous, and obscure as an ongoing interstate war where the West is directly and indirectly involved.

I will only briefly touch upon the subject of Russia’s Armed Forces future, only to argue that although it is the Future we are, and should be, interested in, we should not forget the past when we build up our forecast and foresight models. Moreover, we should keep in mind that the future Russian Armed Forces will not be solely based on lessons learned. It is based also on wide variety of other political, economic, and cultural interests which necessitate a multidisciplinary and comprehensive approach in studying the future of the Russian Armed forces.

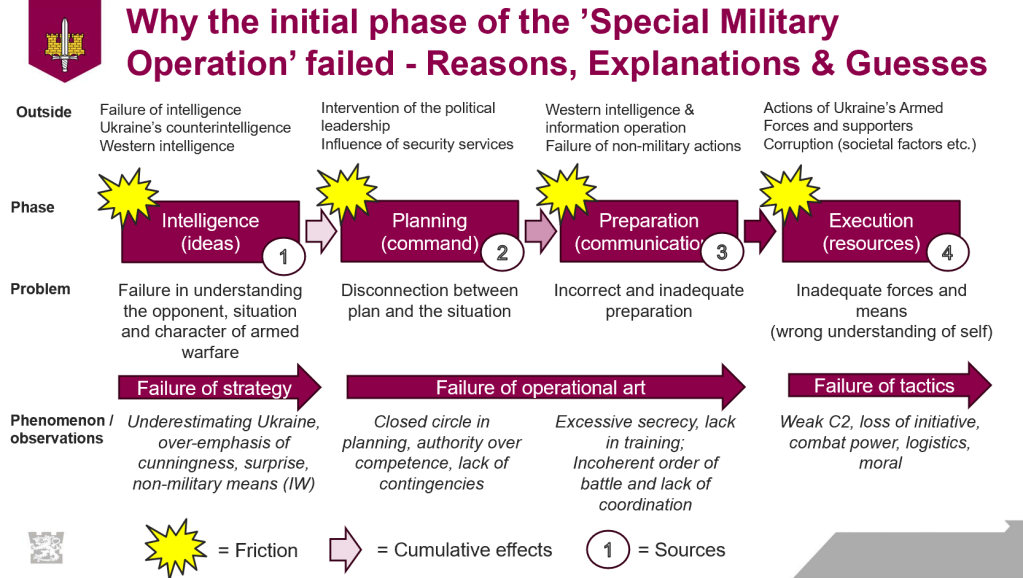

By now, reasons for the Russian failure have been found in every phase of the operation: intelligence, planning, preparation, and execution. Some of these explanations have been related to the inner nature and character of the Russian Armed Forces: to the “wrong” ideas about the future character of war, to the hierarchical command culture or to the Armed Forces leadership’s need to please the political leaders, to the failure to communicate the mission, and to the lack of resources, which was supposedly a surprise to the Russian military leadership, and poor tactics derived from incompetence.

However, some reasons have been found outside the Armed Forces. These issues have caused friction in the planning and execution of the military operation. They have denied the military the required situational awareness to plan an operation or even given the military unachievable objectives for the operation. They have degraded the efficiency of the Russian military or restricted the freedom of warfare in such a way, as to make the achievement of objectives difficult. These outside factors have been related to the opponent (Ukrainians), third parties (the West), other Russian actors (FSB), or the failure of non-military actions to prepare the battlefield, or Russian cultural and societal factors like corruption.

The outside and inside factors for failure have caused, depending on the explanation offered, different kinds of problems for the Russian Armed Forces: The Armed Forces failed to understand their opponent and prepared for the wrong war; there was a disconnection of the plan and military realities; there were incorrect and inadequate preparations made; and there were inadequate forces and means present for the mission (basically the leaders did not know their own forces). Any one of these failures in themselves could have been fatal. However, many researchers have proposed multiple causes for the failure – usually from strategic to tactical level. Some have proposed that the failure belongs to the political leadership and the intelligence services supporting them. Others have argued that the military failed in planning and operating its forces efficiently, even though the forces themselves were good enough. Yet others have pointed out that the forces themselves were materially and morally rotten, and their junior leadership was incompetent – but the plan itself was basically sound or at least made sense.

When analysing all these, probably valid, explanations, we need to keep in mind that the proposed causes of failure accumulate from intelligence, through planning and preparation to execution. Thus far, we have found internal and external causes, on different phases and on different levels, which have separate and cumulative effects and may be either rational, ideational, societal, or material – for the failure of the initial phase of the ‘special military operation.’

This cornucopia of explanations reflects the intense intellectual effort of trying to understand the ongoing war. But there are some problems: First, it is apparent that we do not currently have the necessary sources to compare the explanations and establish their validity. We have access to some sources and not to others. Thus, we could end up explaining issues through the data we have, not through the data we need. Secondly, it becomes too easy to pick and choose the explanation one wants. If you believe that the Russians are bad at mission command – you can point out how 90th Guards Tank Division was mauled in Brovary. If you believe the FSB and Putin are responsible – you can blame false intelligence and authoritarian decision-making. If you want to build certain kind of Defence Forces yourself – you can point out everything what Russia apparently did wrong and what should therefore be avoided. Thirdly, in some cases, of course not in every case, we end up enshrining some explanations to canon – because somebody had some access to some precious source and made a reasonable explanation out if it – only to find out five or ten years later that the explanation was only partially correct or totally incorrect. And fourthly, it becomes hard to do any kind of serious forecasting or foresighting on the development of the Russian Armed Forces if we cannot discern a reasonable amount of non-intertwined, data-based drivers.

These are all problems we face when trying to study opaque societal-human phenomenon when it is happening. Often, I think, it becomes more an effort of intuition than science. The only cure are we, the researchers, critically thinking about our own and our fellows’ explanations, voicing our concerns when something does not meet the scientific expectations, we set for ourselves.

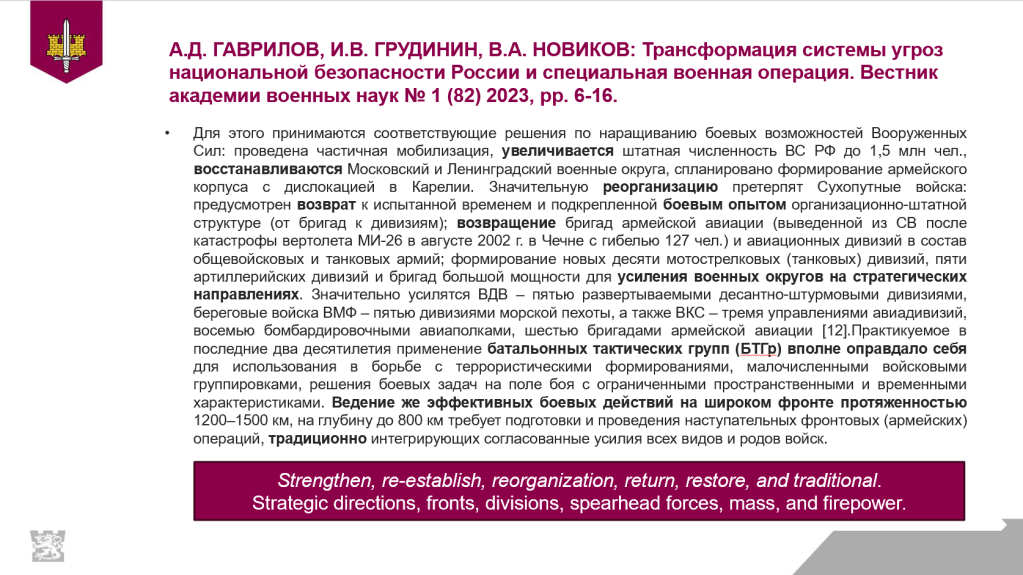

So, what about the Russia’s Armed Forces future? Here is something that they themselves are saying. Professors Gavrilov, Grudinin, and Novikov from the Militaryspace Academy list many different ways of how the Russian Armed Forces will be developed. They use words like strengthen, re-establish, reorganize, return, restore, and traditional. They make the argument that for twenty years the Battalion Tactical Groups (BTG) were the correct solution. Now however, front operations with armies and divisions in strategic directions are back in business. It would seem that the professors are arguing that large-scale conventional war is the guiding principle for developing Russian armed forces. This war will be fought with mechanized infantry, tanks, fighters, and airborne troops – apparently the Navy does not merit a mention.

To understand what these professors are really writing about one needs to study Soviet military history and terminology. One also needs to understand what kind of process created the BTGs to understand what changes and what stays the same in Russian military thinking. Because the Armed Forces do not operate in a vacuum, it is not enough to understand military thinking or history; society, culture, economy, technology all change and affect the ways in which it is possible to develop armed forces. Also, whatever is argued through old terminology cannot escape the change of machines and methods. Meanings change behind the terms. There is a need for hard data, professional expertise, understanding of technological realities, and mathematical calculations to put that which is said into the context of reality. Otherwise, we just end up reading military academic journals in a solipsistic circle.

This text is based on a presentation given in the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, 24th June 2024.